If you’re reading this, you’re probably an accomplished reader. In fact, you’ve most likely forgotten by now how much work it took you to learn to read in the first place. And you probably never think about what is happening in your brain when you’re reading that email from your boss or this month’s book club selection.

And yet, there’s nothing that plays a greater role in learning to read than a reading-ready brain.

As complex a task as reading is, thanks to developments in neuroscience and technology we are now able to target key learning centers in the brain and identify the areas and neural pathways the brain employs for reading. We not only understand why strong readers read well and struggling readers struggle, but we are also able to assist every kind of reader on the journey from early language acquisition to reading and comprehension—a journey that happens in the brain.

We begin to develop the language skills required for reading right from the first gurgles we make as babies. The sounds we encounter in our immediate environment as infants set language acquisition skills in motion, readying the brain for the structure of language-based communication, including reading.

Every time a baby hears speech, the brain is learning the rules of language that generalize, later, to reading. Even a simple nursery rhyme can help a baby's brain begin to make sound differentiations and create phonemic awareness, an essential building block for reading readiness. By the time a child is ready to read effectively, the brain has done a lot of work coordinating sounds to language, and is fully prepared to coordinate language to reading, and reading to comprehension.

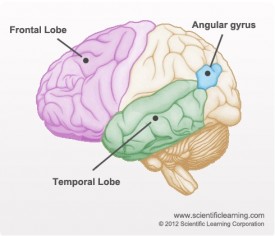

The reading brain can be likened to the real-time collaborative effort of a symphony orchestra, with various parts of the brain working together, like sections of instruments, to maximize our ability to decode the written text in front of us:

- The temporal lobe is responsible for phonological awareness and decoding/discriminating sounds.

- The frontal lobe handles speech production, reading fluency, grammatical usage, and comprehension, making it possible to understand simple and complex grammar in our native language.

- The angular and supramarginal gyrus serve as a "reading integrator" a conductor of sorts, linking the different parts of the brain together to execute the action of reading. These areas of the brain connect the letters c, a, and t to the word cat that we can then read aloud.

Emerging readers can build strong reading skills through focused, repetitive practice, preferably with exercises like those provided by the Fast ForWord program.

Independent research conducted at Stanford and Harvard demonstrated that Fast ForWord creates physical changes in the brain as it builds new connections and strengthens the neural pathways, specifically in the areas of reading. After just eight weeks of use, weak readers developed the brain activity patterns that resemble those of strong readers. And, as brain patterns changed, significant improvements for word reading, decoding, reading comprehension and language functions were also observed.

It’s never too early to set a child on the pathway to becoming a strong reader. And it’s never too late to help a struggling reader strengthen his or her brain to read more successfully and with greater enjoyment.

It’s all about the brain. Have you hugged your brain today?

Related Reading:

10 Ways to Help Your School-Age Child Develop a “Reading Brain”

Phonemic Awareness as a Predictor of Reading Success