What is the mark of a good student? Is it innate intelligence? Is it attention span? Is it drive? Studies show that a major contributor to success might be as simple as having self-control. Take, for example, the marshmallow experiment.

Place a single marshmallow in front of a four-year old. Tell them they can eat it now or wait 15 minutes and have it along with a second marshmallow.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Walter Mischel of Stanford University performed this very experiment with over 500 nursery school children. What percentage do you think was able to control their impulses and hold out for marshmallow number two? In the end, fewer than one in three children were able to wait it out for the two marshmallows. At four years old, they simply had not developed the ability to delay gratification required for the challenge.

Paired with recent follow-up studies with 155 of the same individuals, the marshmallow experiment has come to shed fascinating insights on the inner workings of motivation and gratification, and how the two contribute to future success in school and life.

In the end, these studies have shown that children who were able to resist that first marshmallow were also more likely to be able to “avoid substance abuse, maintain a healthy body weight, and even perform better on the SAT than peers who couldn’t resist temptation.” In another study by Angela Duckworth at the University of Pennsylvania, self-control was a better predictor of academic success than IQ.

Self-control: Innate or teachable?

Given the proven connection between self-control and life success, the question arises: Is it possible to develop tools that help people enhance self-control?

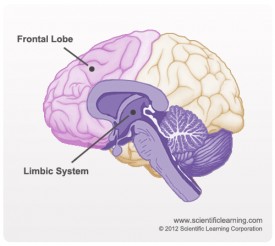

As it turns out, self-control is the result of processes in two parts of the brain. Our rational thoughts, such as “If I wait, I get the second sweet,” take place in the pre-frontal cortex. More urgent decisions take place in the more primitive ventral striatum. Decisions like these that connect to deeper desire and reward depend on the environment around us. In this second case, the thought process might be, “Gee, that marshmallow sure looks soft, sweet and yummy, and I really want it. Right now.” Research has shown that the rational thoughts can often be derailed by the primitive limbic system; this is no surprise, given the importance of these systems to the survival of our species over the eons.

So, canwe strengthen the ability of the rational side to win out over the impulsive side? One solution might just lie in helping young people change how they focus on the environment around them, such as helping them differentiate between “hot” and “cool” cues. The limbic system deals with “hot” cues, activating emotions like impulse, anger, sadness, happiness and satisfaction. On the other hand, “cool” cues are processed in the frontal lobe and activate cognitive systems that control functions like planning, problem solving, working memory and reasoning. Returning to a variant of our marshmallow experiment, studies have shown that students who were coached to focus on “cool” attributes like color or shape were better able to resist temptation than those who focused on “hot” cues like taste.

Toward impulse-control interventions

Research is now underway to figure out how educators can better harness some of these insights into the power of impulse- and self-control to help students better achieve success. At the KIPP Academy School in New York, the marshmallow experiment has been used as a way to initiate discussions about self-control with 6th graders and help them make better, more rational decisions.

Ultimately, the ability to produce concrete strategies and tools that help students learn to control their impulses will depend upon the results of investigations that are still in the works. But eventually, if we are taking the research to heart, success will likely follow.

For now, if your students seem a bit impulsive from time to time, a chat about marshmallows might be just the thing to get them thinking.

Further Reading:

Study Reveals Biology Behind Self-Control

Related Reading: