As an educator, I want to see students putting forth the absolute best effort they can, each and every time they attempt a task. But what might happen if we created a classroom culture where making mistakes were more integral to the learning process? What if failure were discussed openly and positively as a key part of the learning experience?

In most traditional schools today, when we look at the grade system,

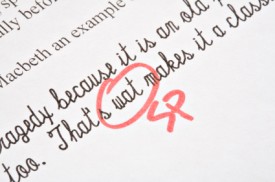

A-B-C-D-F, we see the F at the bottom of the scale. It says, “You’ve attempted this task and not performed up to standards.” There is little to no upside to the grade. It is the label we give to an effort that has delivered a less than satisfactory performance. For the person who has received it, it is a dead end. It can be painful and embarrassing, dragging down his self-esteem and reinforcing an image of himself as a failure.

As educators, the trick for us is to turn each of these moments--each of these mistakes and failures--into a beginning and a learning opportunity, and cultivate that same perspective in our students’ minds as well. Scientifically speaking, at the moment of failure, the brain is primed to absorb the information needed to perform the task successfully the next time around. In short, when we have the perspective that we can learn from our mistakes, parts of the frontal lobe are engaged when we make errors and that helps draw attention to those errors. (See Motivation to do Well Enhances Responses to Errors and Self-Monitoring, Bengtsson, Lau and Passingham, 2009.)

What if we became more cognizant of these ideas and harnessed their power in the classroom?

For a moment, suspend your image of the classroom where statements like “I must always get the right answer” represent the mindset. Instead, imagine a classroom designed around statements such as:

- “While I will learn by studying and listening, I will learn the most by doing.”

- “I will demonstrate my abilities through successes, but I will learn through my mistakes.”

- “Mistakes are a way for me to get feedback so I can do it right the next time.”

- “This classroom is a safe place where I am encouraged to try, to experiment, to fail and to use those failures to learn even more.”

Interestingly, these statements embody a “ growth mindset,” which we wrote about last year. In short, based on the research of Carol S. Dweck of Stanford University, if we teach students to be go-getters who face challenges as learning opportunities with open-mindedness as opposed to a fear of failing, their brains are more apt to learn effectively.

It is essential to note that in such a classroom, making mistakes would be clearly differentiated from carelessness and lack of effort, which would not be tolerated.

What would it be like to learn in such a classroom? Students would be encouraged to develop and try new ideas. Getting a wrong answer on a math test represents an opportunity to go back and learn a better way of solving the problem. Students in this classroom learn science by getting out and experiencing material directly in the field. They learn to USE the scientific method as opposed to reading about it in textbooks or performing formulaic lab demonstrations.

What kind of professional might that person grow to be? Imagine the mindset of the student who comes out of a system founded on these ideas. This person is an innovator who has little fear of trying new ideas. This is someone who has been encouraged to think outside the box. This is also a person who, when she makes mistakes, sees them as a moment to learn and improve. Each failure represents a look ahead to the future. This person sees herself as a problem-solver.

As countless economists, sociologists and other thinkers have posited, the future will be owned by those who can innovate, to try new ideas and, certainly, risk failure. These are skills that we can and must impart to our students. And we can start doing so by more highly valuing the making of mistakes and transforming them into powerful teachable moments.

For further reading, check out: