Dyslexia is thought to affect a high percentage of people. The condition can be caused by biological changes during brain development (known as developmental dyslexia) or by environmental effects such as illness or injury (known as acquired dyslexia). In their recent article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Nora Maria Raschle, Jennifer Zuk and Nadine Gaab cite estimates that developmental dyslexia affects between 5 and 17% of all children. (2012) They further outline how it can have detrimental effects on a child’s life both inside the classroom as well as beyond.

For these reasons, educators and researchers have placed intervention strategies for developmental dyslexia very high on their priority list.

While much progress on such interventions has occurred in the area of helping individuals with developmental dyslexia once they have been diagnosed, other research is delving into identifying the neurological and physiological differences between brains that develop the condition and those that do not.

To find out if there are identifiable predictors of developmental dyslexia, Raschle, Zuk and Gaab examined the functional brain networks during phonologic processing in 36 pre-reading children with an average age of 5.5 years. That is they were looking for brain differences even before any of the children had learned to read since previous brain studies of dyslexia have been conducted on individuals after they have begun to read, albeit poorly. All of the subjects were of a similar socioeconomic status; most came from homes with relatively high SES and strong language skills. These are the type of home environments that typically result in the development of good language and reading skills.

The only substantive difference between the groups in this study was that half of the subjects had a family history of developmental dyslexia, while the other half did not.

Interestingly, the 18 children with a family history of dyslexia scored significantly lower than those who had no family history on a number of standardized assessments, including:

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF), Core language

- CELF, Expressive language

- CELF, Language structure

- Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP), Elision

- Rapid Automatized Naming (RAN), Objects

- RAN, Colors

- Verb Agreement and Tense Test (VATT), Repetition

Not only did the research team examine the two groups’ performance on these evaluations, but they also used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning to identify what was happening in the brains of each learner during the examinations.

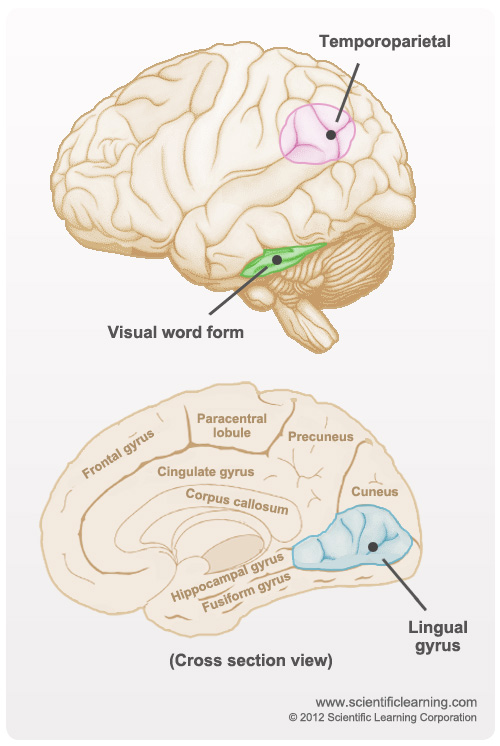

Brain activity in the left lingual gyrus as well as the temporoparietal brain areas correlated with phonological processing skills. Interestingly, the team discovered that members of the group with a family history of dyslexia showed a reduced activation in these areas even before learning to read. Their discoveries suggest that the left temporoparietal region of the brain in this group reflect an inability to map phonemes to graphemes. In other words, their brains simply were not adequately developed to match language sounds with their written counterparts. In addition, this same region of the brain – also known as the “visual word form area” – seems to be involved in processing words during reading in both children and adults.

The authors unequivocally state, “Developmental Dyslexia can have severe psychological and social consequences, potentially negatively impacting a child’s life.” All too often, we identify learning disabilities much too late. In the case of dyslexia, we might make such a diagnosis and begin interventions halfway through elementary school, but by then we have much catching up to do. If these students’ vocabulary skills and motivation to read have already been compromised, the climb back may be much more difficult than if had the situation been identified earlier.

Research like that of Raschle, Zuk and Gaab will help us begin to address learning disabilities at the neurological and physiological levels much earlier in life. Through very early diagnosis and intervention, we may one day be able to more effectively ameliorate – and maybe even eliminate – the distressing experience of developmental dyslexia.

Read this study to learn how Fast ForWord helped significantly improve reading skills in children with dyslexia.

References:

Gaab et al., 2007, " Neural correlates of rapid auditory processing are disrupted in children with developmental dyslexia and ameliorated with training: An fMRI study,"; Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience 25, 295-310.

Raschle, N. M., Zuk, J. and Gaab, N., 2012, " Functional characteristics of developmental dyslexia in left-hemispheric posterior brain regions predate reading onset." PNAS, v. 109, p. 2156–2161.

Related Reading:

Dyslexic Learners Dramatically Improve Reading Skills with Fast ForWord

Increased Brain Activity in Reading-Related Areas After Using Fast ForWord Language